Traditionally, massage therapists use a “pain scale”. This helps us communicate with our clients/patients, and helps us to understand the experience they are having. It can help us know if we can adjust pressure as needed, or to modify, or stop treatment.

We’ve all used it at some point. This is the one the I learned in school, and I’m quite certain that it is reflective of massage therapy culture in this province, and possibly the country.

1 is a light touch

2 is a bit more pressure

3 is a “therapeutic pressure”, or “a good pain”

4 is painful, but you can breathe through it

5 means stop.

This kind of verbiage is ubiquitous, and it is problematic.

The words “therapeutic pressure”, or suggesting that a “therapeutic pain” is important for treatment incorrectly implies, that the other pressures aren’t therapeutic, and that massage must be a certain pressure to be effective.

While having an inspiring chat with a colleague, it occurred to me how strange it is that we ask our patients to communicate their subjective experience of massage therapy using a scale which is entirely focused on how much it hurts.

It’s entirely pain centric. It’s even called a “pain scale”! It’s curious to me, how that’s how we’ve chosen to measure the value of the experience. I can’t help but wonder what kind of experience this is setting the patient up for.

What if we used that same strategy somewhere else, like say, in a restaurant?

Imagine you’re a server at a restaurant, and you wish to understand how your customers are enjoying their food.

When you ask them how they’re enjoying their food, would you ask them how bad their food is, or how uncomfortable they are?

In order for me to help my patients have the best experience, or help them get the subjective experience that you’re looking for, I have to trust that they’re telling me the truth.

It’s also the therapist’s responsibility to try to create an environment where the patient feels comfortable enough to ask for what they want, which can be challenging.

Maybe on another blog, I will explore why we feel so uncomfortable asking for what we want, but I digress.

Being a clinician helping someone navigate their uncomfortable experience almost seems analogous to a scenario where we are trapped in a dark maze together.

I might know a better way out, but I recently lost my sight.

You have a flashlight, but don’t know the way.

It takes some work, on both our parts to trust each other, and work together.

Anyone familiar with my work probably knows that patient centred care isn’t just a new trend. It’s part of my ethos.

One of the ways I practice patient centred care is that I believe the best massage is the one that feels the best for my patient.

When it comes to technique, there’s no objectively best way to give a massage, and no technique offers superior outcomes.

I think the best way is the way that the patient likes best.

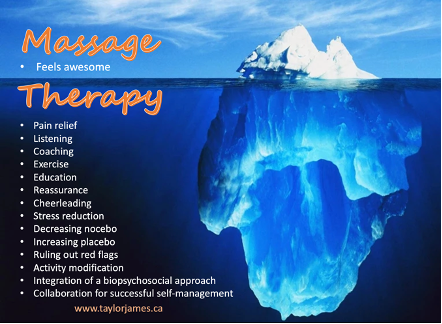

People come to massage therapy for the therapeutic relationship, coaching, encouragement, and reassurance that their back pain is just back pain and not something scarier.

We can help them increase their functional ability in their activities of daily living, and people also come to us for touch in and of itself.

My journey as a clinician has gone from wanting to correct and change bad posture, to changing tissue (like tight muscles), to changing pathological movement patterns (like scapular dyskinesis or a hamstring dominant hip extension patterns), to changing unhelpful narratives adopted by patients.

Now, I just hope to change their experience. Instead of blaming the anatomy, movement, alignment, or posture, now I just hope to change the way it feels.

But how do we do that? How do we tap into a person’s subjective experience, so that we can create a more positive experience? This got me thinking about pleasure.

When I changed my practice to be more patient centred, I started inviting my patients to help train me to give them the best massage. I noticed that patients are sometimes confused

by this power reversal. They’d sometimes look at me with an expression that seemed to say, I don’t know, aren’t you the expert?

In some ways, sure. I am a highly trained health care professional, who’s area of practices focuses on musculoskeletal care, but where I need my patient’s help is that I don’t know what they’re experiencing.

I don’t live in your body, and can’t access that subjective experience, so we must build a bridge.

I literally ask my patients if they will help train me to give them the best massage, so that the time we spend together is high value for them.

In recent years, I started checking in with my patients in a different way.

Now when I check in, a conversation with my patient receiving massage (PRM) might look something like this:

Me: ….and how is what I’m doing working for you?

PRM: It’s okay.

Me: Okay. Thank you. Maybe I can adjust the pressure? Would you prefer a little more, or less?

PRM: Actually, yes please. I’d like some more pressure.

Me: Okay, thank you for saying so. Let’s try a little more, and see if you like that better…(after adjusting the pressure) …and how’s that working for you now? A little more? A little less?

PRM: (emphatically) Oh, that’s perrrrfect! Thank you!

Me: Of course! It’s your massage! If we can go from okay to good, or good to great, would you please help me to be able to do that?

I’m sad that so many people have confessed to me that they didn’t know they could ask for what they want.

If you’re a massage therapist, I’d like to ask you a question.

Do you help your patients experience pleasure?

When I asked you that question, did you feel uncomfortable?

Did you feel your body tighten up?

Maybe we should ask ourselves why. Pleasure is good!

The science of pleasure is categorized into eudiamonic, and hedonic.

Eudiamonic is the type of happiness or contentment that is achieved through self-actualization and having meaningful purpose in one’s life.

Hedonic is the type of happiness or contentment that is achieved when pleasure is obtained, and pain is avoided.

I think massage therapists have the opportunity to influence both! How incredible!

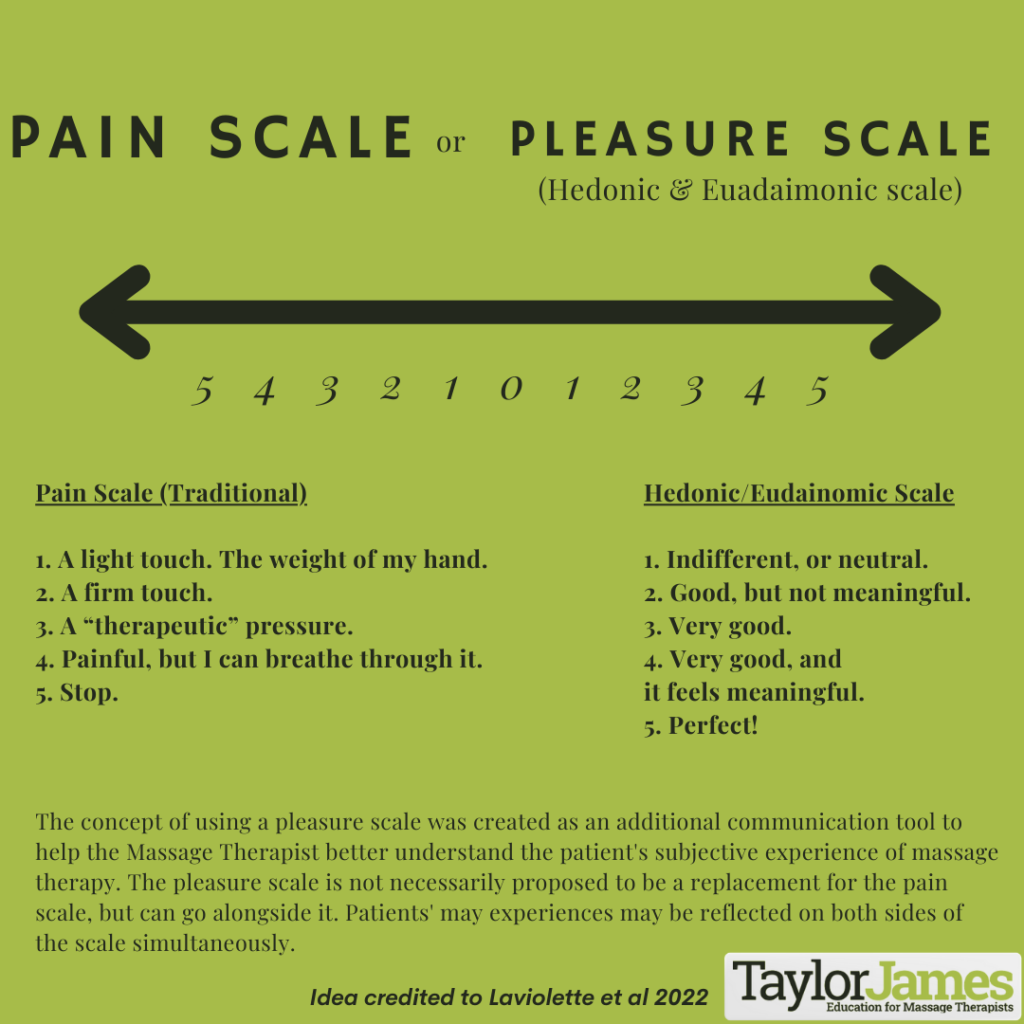

Here’s what I propose as either an addition to, or in replacement of the traditional pain scale.

This is a work in progress, and I understand there’s lots to talk about. We humbly offer this little idea to the community, and very much look forward to the many conversations and challenges we anticipate with the proposal of this idea!

You know, after 15 years, the breakthroughs are fewer and farther between, but I think we’ve got something special here. Since I’ve been using this, instead of a pain scale, patient experience has changed a lot. It’s been a really positive experience for both myself, and the patients I see.

What about the science of pleasure?

It’s dope. It’s also super similar to pain science.

Most of what is known about pain and pleasure comes from the study of those things in isolation, and once I started digging into a bit of research on pleasure, it was interesting to discover that pleasure and pain have remarkably similar biological substrates.

In other words, pleasure and pain have similar neuro and hormonal circuitry. They also share similar processing areas of the brain, but people do not have similar experiences. Isn’t that interesting?!

Could pleasure and pain be more similar the different?

My understanding of the literature on this super cool subject is that our differences in personal experiences with pleasure and pain is due to what is called “subjective utility” (links here, and here).

Pain is a deeply personal, and entirely subjective experience that an external person cannot access or understand.

Here’s an example.

This is just like when you have that good sore feeling after leg day, and you might laugh about it the next morning when you can hardly get off the toilet.

The pain isn’t disabling, and your overall experience is that you’re proud of yourself, and you know that it

was for a good reason.

That soreness represents your hard work, and you feel good about yourself.

Overall, you think this is a really good experience.

You might even say, for more than one hot minute, that it’s pleasurable.

What if you like chilli peppers, and you enjoy pleasure spiked with pain?

(Reference to the Red Hot Chilli Peppers song Aeroplane (One Hot Minute – 1995)

Just ask a hot-sauce lover. They’ll tell you that it doesn’t burn, and that it’s not unpleasant in any way.

Who am I to say what your subjective experience is?

I trust you to manage that. I am here in service to the way that you want to feel when you leave.

Before I get a bunch of messages with people saying that it’s not that simple, and send me a bunch of papers on DNIC, proposing that painful treatments can dial up pain sensitivity, you can relax. I’m not suggesting that we don’t help guide our patients’ choices.

All I’m saying is that if we’re driving somewhere together, as patient and therapist, they have the wheel, and we’ve got a map. The therapist rides shotgun.

Sometimes I view my role, as a massage therapist, kind of like, if paracetamol could give you great advice, and a hug.

Pleasure represents the subjective hedonic value of rewards. Pain is about both the hedonics (suffering) and motivational (avoidance) aspects of a painful experience.

Seeking pleasure and avoiding pain is important for survival, and these two motivations probably compete for preference in the brain.

Maybe it’s about risk vs reward.

Research on the subject of risk and reward shows accepting a reward at the cost of receiving a nociceptive stimulus decreases the experienced intensity of the stimulus. Conversely, rejecting such a reward in order to avoid the nociceptive stimulus increased the perceived intensity of the nociceptive stimulus.

In plain speak, behavioural sciences demonstrate if you believe it’s worth it, that belief in and of itself changes the pain experience to a more positive one. Anything that is evaluated as more important than pain in a specific situation should have anti-nociceptive effects.

In contrast, if the pain is viewed as more important, pro-nociceptive effects should occur.

These effects are presumed to be exerted via engagement or inhibition of descending opioidergic pathways, respectively.

This is all in line with reward-induced pain inhibition that has been demonstrated in animal and human studies.

This reinforces for me that it’s the experience that we need to change, but how do we massage someone’s subjective experience? First, we’d have to take this journey in partnership.

One closing thought. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: The definition of pain, by the International Association for the Study of Pain is “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.”

I see my job, as a massage therapist working with people living with pain, as creating a pleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with actual or potential change.

Thanks for reading!