An Example for RMTs on How the Orthopedic Model Debunks Itself.

This post will be different in the way that I will use absolutely no scientific research or even any evidence to support my points here. I will only use what’s in the orthopaedic textbooks that we use to educate RMTs in the regulated provinces in Canada.

The textbooks I’m referring to can be found here and the list of them is called the Recommended Resources for board exams. https://www.cmtbc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Recommended-Resources-for-Exams-2021.pdf

Point of this post

You don’t need fancy shmancy science to see how flawed the orthopaedic model is.

This post attempts to demonstrate that the many of the foundational models we are taught as RMTs (and potentially all MSK practitioners) in Canada contain within them competing premises that can’t rationally exist at the same time.

Like I said, you don’t need science or research to debunk the ortho model. All you need is to know the ortho model thoroughly. If you try and apply it using it’s own rules, it soon becomes obvious that it doesn’t even support itself.

As you read, please understand that I am speaking in the voice of someone who was trying to make these models work for too many years. There are huge gaps in the logic here, but that’s kind of the point. I’m hoping to make it obvious. Hopefully this illustrates my point! If this goes well, I will make a whole series of them. I’m really looking forward to hearing what you think!

First up in this series! Janda’s Cross Syndromes.

Summary of the premise.

People will often appear in postural positions that have an increase or decrease in the spinal curves in the sagittal plane.

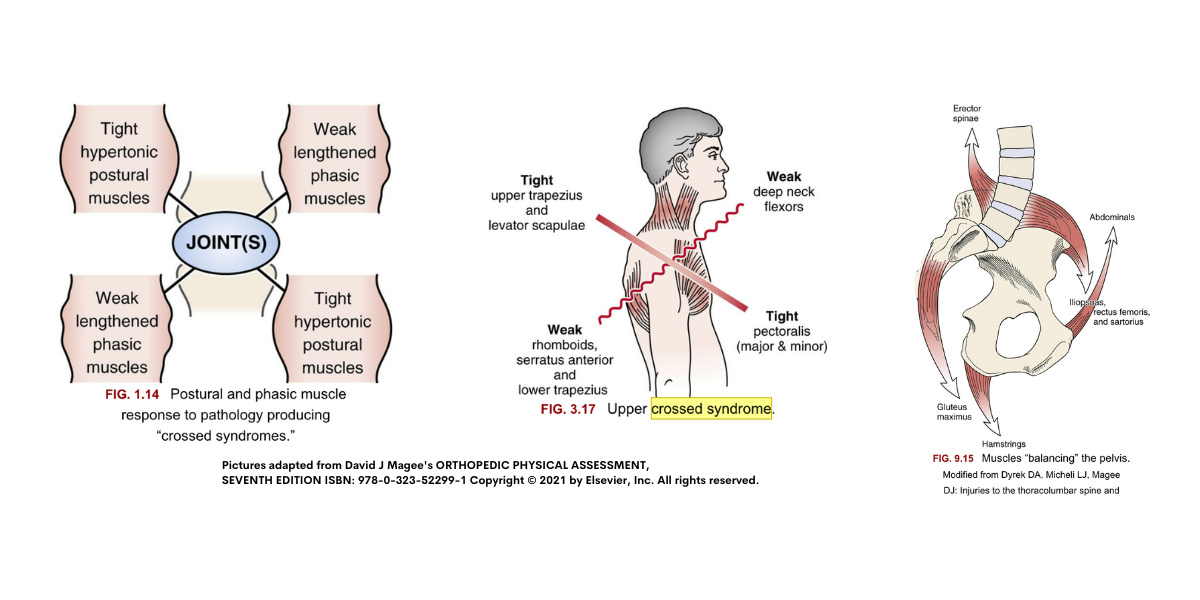

When we see this in the upper back, neck and shoulders, we call it Upper Cross Syndrome, or sometimes Shoulder Cross Syndrome.

In the lumbar spine and pelvis area we call it Distal or Lower Cross Syndrome.

It is characterized in the upper back, neck, and shoulder area by a head forward posture, craniocervical extension, a hyper kyphosis, scapular protraction and downward rotation at the scapulothoracic joints, and internal rotation at the glenohumeral joints.

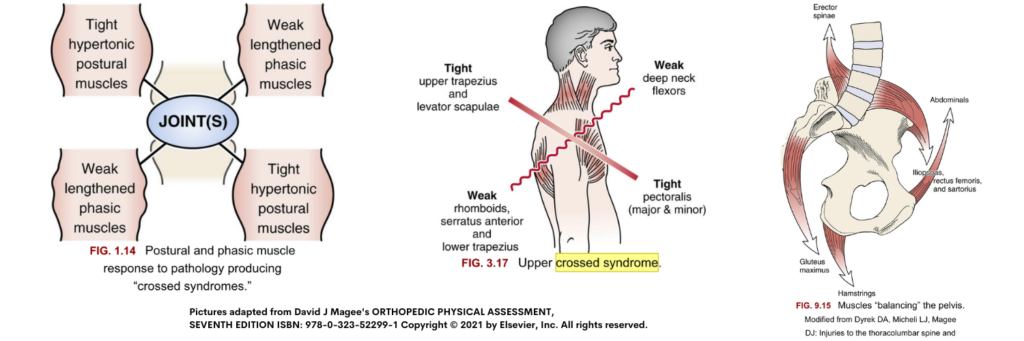

In the Lumbar and pelvic area, it is characterized by a hyper lordosis, and anterior pelvic tilt. The muscles in these position are said to be ‘tight’, “short and strong”, or dominating the pattern on one side, and on the other side they are said to be ‘weak’ or inhibited. Please see picture below for details.

How it debunks itself with our own material.

We learn muscle length testing and strength testing (manual muscle testing) according to the book Muscles.Testing in Function Posture and Pain, by Kendall, Florence, Peterson, and Kendall.

Let’s give an example of how I used to practice in about 2008, and you will see quickly how the theory falls apart.

A patient comes in, and they have a chief complaint of lower back pain. I see that they have a hyper-lordosis, and they also have an extension sensitive lumbasacral area. I suspect that the reason is because they have been walking around with their facets rubbing together and their poor unstable SI joint must be cranky from walking around in a loose packed position all day. Obviously they have tight hip flexors, errectors, and their glutes and abdominals are weak, right?

So, what did I do?

Because I’m a good little clinician, I wanted to investigate further!

In the best interests of my patient I needed to know about how much stretching I should apply to the tight side, and how much strengthening to apply to the inhibited side.

If we’re going to proceed with this premise being true, it’s conceivable that it could be mostly tightness on one side, or mostly weakness on the other. Maybe it was about 50/50. Maybe it was 100% all about weakness on the inhibited side, and exercise was the best use of our time to fix the problem?

Kendall’s book defines tightness by saying that an available range at a joint should reach at least 80% of the available range of motion in order to be considered normal.

If something is tight, it should be limiting range of motion in the direction of stretch. If upon examination range falls below the 80% this is justifiably tight and stretching is indicated.

For example, Magee says that normal hip extension is 10-15 degrees. Even if you’re doing a great job stabilizing the pelvis to isolate as much acetabularfemoral motion as you can, if your patient has any available passive hip extension, a tight psoas can not be the reason they have a hyper lordosis.

Know what I’m sayin’?

Side note…if you’d like to watch a free video about why the psoas can’t flex or extend the lumbar spine anyway, you can find the link here. https://www.themtnetwork.com/courses/the-one-about-the-psoas

Okay…so if the psoas isn’t tight, then the hip extensors must be weak, right?

Go ahead and manually muscle test! Even if you think you’re pretty good at it, I think you’ll find that the results don’t support a hypothesis of a cross syndrome. I mean…is a grade 4 really clinically relevant weakness? Sounds shakey at best. See what I did there? 😉 A little ortho humour. If you know, you know…but I digress.

Same reasoning goes with the idea of having “tight pecs”. How many times do you see people doing doorway stretches, because they purportedly have tight pecs? Spoiler alert! If you can externally rotate to 80-90 degrees, and horizontally abduct your arms passed the coronal plane, tight pecs can’t logically be the reason why you have an upper cross syndrome.

If you’re still skeptical, I challenge you to assess for yourself,

but strictly by protocol! I think you’ll find that it just doesn’t add up.

In closing, I’d like to add that I grew up surrounded by people from the Caribbean, and West Africa. I grew up on Jamaican Dancehall, and Soca music and dancing. Truss me guy, if having a hyperlordosis was bad for our bodies, half of the Caribbean would be crippled!

Keep dancing!