If you’re into using IASTM, that’s great. Keep using it. Keep on serving your community, and your patients. I know you’re doing an awesome job!

Yo, if I was working with athletes, I’d probably have a bag full of those BBQ tools, because that community seems to like it.

I just have some questions about the common explanations of how it’s supposed to work.

I’m sure that it works for a thing or two. I just don’t think that it works *how* a lot of people say that it works.

What does the literature say?

Are the popular narratives biologically plausible?

How is this clinically relevant?

Let’s start with a bit of an overview of the literature.

What does the research say about the effects of IASTM on pain, and range of motion?

IASTM has no special effect, (1, 2, 3, 4), it has a minimal effect, is part of a protocol where there is a combined effect.

Bummer. Or is it? I guess it depends on how you look at it. If we just think about it as just another way to massage people, and if you like it and they like it, awesome! We don’t need special stories to justify how we might think it works. What’s wrong with just saying it works for me?

If you wanna get critical about the information, however, it brings up interesting questions about popular narratives, and why we’re so attached to making things more than they are.

It says two main things.

- Alone, it doesn’t do anything that any other forms of touch, movement, or self-massage don’t do. It can slightly improve range of motion and have a small but significant pain modulatory effect.

- Many of the studies on IASTM are low value, in the way that they don’t have a control group, which only shows that doing something is better than doing nothing, or it is used in conjunction with other modalities such as exercise, so we don’t have any understanding of its effects alone.

In summary, if you like using IASTM, ASTM, or GuaSha, that’s great! I’m sure you’re doing a great job serving the needs of your patients. However, when it comes to making claims about treating scar tissue, increasing strength, or suggesting that it’s superior in any way is simply not justifiable.

Adhesions?

Where are these adhesions that we are said to be treating? I think that it’s fair to say that most believe that they are somewhere around the muscle layers, or in the deep fascia. Cool. Let’s just look at why maybe that reasoning isn’t logical.

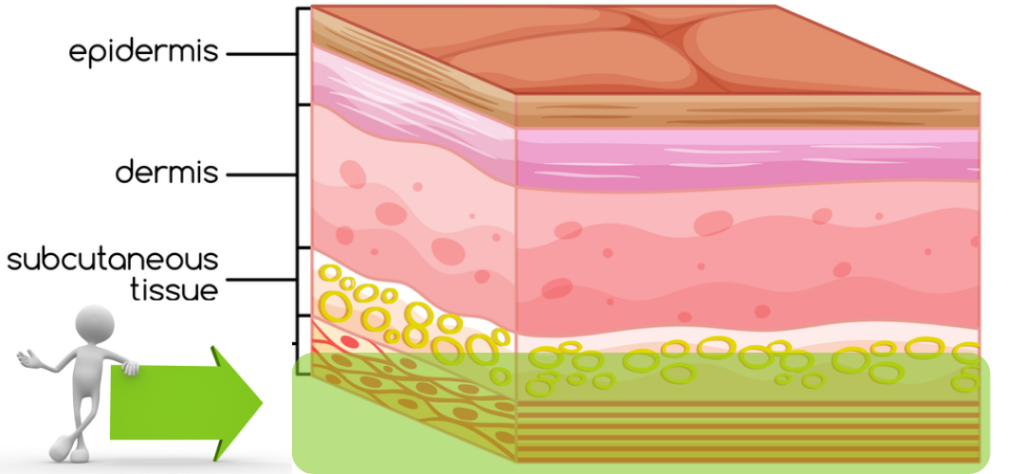

We apply the massage with the tools here, on this layer of the tissue, ya? Where are the so-called adhesions we are supposed to be working on?

Here-ish? (See highlighted green area)

The common beliefs are that the adhesions are on top of, invested in, are between the deep fascia and the muscle, or are in between the muscles or their individual fascicles. None of these hypotheses have been validated, but let’s proceed with this for a second as if that was true, and see what happens.

What is the deeper fascia made of? Denser connective tissues that might be more or less regularly arranged to facilitate a little, to next to no, movement. They are very strong.

We are supposed to be scraping through softer stuff to break up tough stuff that’s adhered to, or underneath, tough stuff.

The logic here just doesn’t track. If we wanted to scrape gum off of the pavement, through a pillow-case and a pillow, could we do it without damaging the pillow or case?

Why is this not happening?!

Seeing how we don’t routinely rip open patients, something else must be going on.

It’s doing something for sure, but the popular stories about assessment and treatment of myofascial adhesions just aren’t possible.

It is said that IASTM breaks down scar tissue. The research on massage and scar tissue is weak, at best, but even if we were to try and logic our way through this one, we’d run into the same problem as above.

When we’re using our critical thinking skills, as health-care professionals, we should first ask ourselves if the hypothesis is biologically plausible (thanks to Eric Purves for that succinct bit of language). If it’s not biologically plausible, we can dismiss it.

If my first argument isn’t compelling enough for you, let’s take a look at what the literature says.

Studies like these ( one, two, three and four) attempt to validate claims that IASTM increases fibroblast proliferations, and therefore facilitates healing.

I have two main problems with this.

- The assumption that an increase in fibroblast presence indicates better healing. This has not been established.

- What do you mean by ‘healing’?

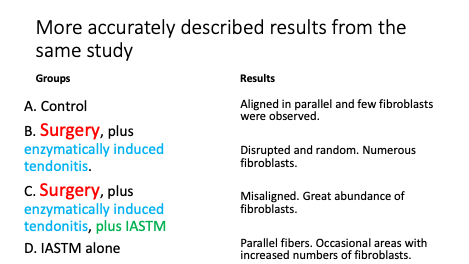

In order to mimic tendinopathy, surgery is performed on the subject (usually a rabbit or rat).

They cut open the leg, and dump in some inflammatory scarring agent to mimic tendinopathy.

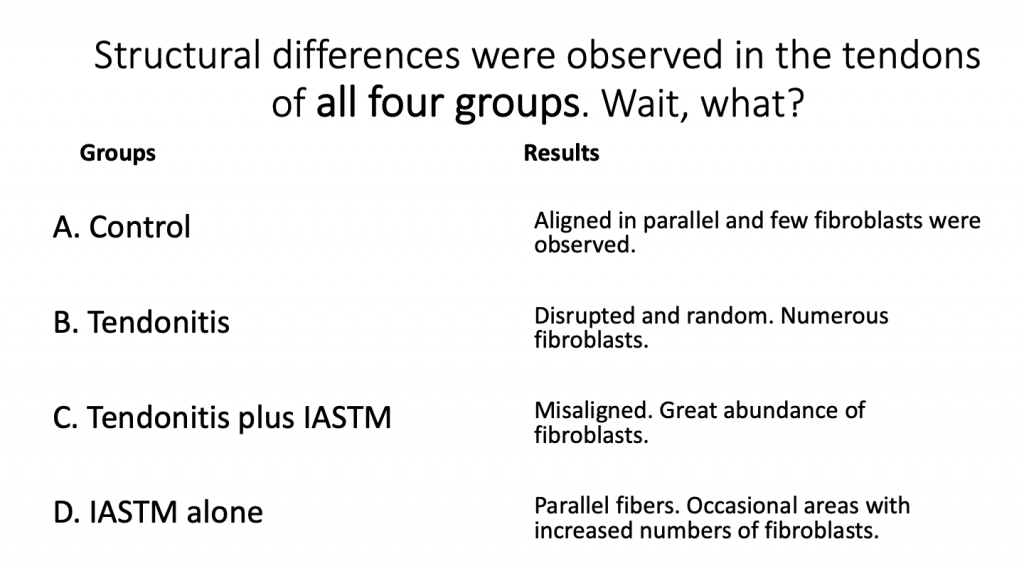

A couple of weeks after surgery, they anesthetize the rats and scrape them for a few minutes with the tool. What happened?

What if I put it to you like this instead?

Is anyone surprised that animals that had surgery had *a little more* fibroblast activity in the area?

So far, I’m not impressed.

Even if we said that increased FB proliferation was a desirable thing, we haven’t established that IASTM is responsible for this.

I’m also still scratching my head about the conflicting claims. IASTM, apparently increases fibroblast activity, so it increases scar tissue? Buuuuuut it also breaks up or removes scar tissue?

Studies like these are also used to suggest that IASTM increases the strength or resilience of the tissue. What did we find?

Tendons that received IASTM were a bit stronger compared to the control. Okay. That seems straightforward until you remember that those tendons had surgery and enzymatically induced tendinopathy.

Is anyone surprised that an area that an area that had surgery is a little less stretchy?

Lastly, I’d like to comment on when studies like the ones above equate findings like this to words like ‘healing’ and ‘recovery’.

What does recovery mean to you?

To me, as a clinician working with people, it means decreased pain and better function.

What better means is up to the patient, and I just help to get them there.

Did they ask the rabbits and mice how they felt? What was their pain like? Did they measure any known animal behaviours associated with pain so that we could perhaps infer that they might be feeling better? No. these measurements are made after the animal is destroyed.

Lemme’ get this straight. You’re saying I’ve recovered and healed, but didn’t ask me how I’m feeling? Ya…okay bud.

It’s neat, but pretty freaking misleading to equate these minor physiological changes to recovery.

Recovery means something different to us, homie.

In closing, I’d like to say that many of the claims made about IASTM are unjustifiable, and we should adapt our currently popular stories of how it works to reflect the research, but hey man…If you like IASTM, and so do your patients, you should continue using it.